Team Lazerbeam’s Crystal Ball shares some insight into south Africa’s growing indie gaming industry.

Crystal Ball, a social anthropologist, conducted research on the socio-spatial entanglements of the Cape Town game dev scene for her master’s thesis and now works as a producer for video-game developers Team Lazerbeam, plus she co-runs the Playtopia volunteer programme – while also working a nine-to-five. She takes us through her first project, Wrestling With Emotions: New Kid On The Block, the sequel to 2016’s quirky life/dating/ wrestling simulator Wrestling With Emotions, and how this new game builds on the first instalment.

You have master’s degree in social anthropology. Why did you choose to study this?

No kid says ‘I want to be a social anthropologist/ethnographer when I grow up!’ It’s the sort of subject you stumble upon or you scan the university’s course catalogue and pick the subjects that are a bit unusual but have words that you recognise, such as ‘society’ and ‘analysis’ and ‘identity’. I always loved writing and I quickly learned that anthropology and ethnographic writing specifically, gave me an outlet for writing with purpose, creativity, and curiosity about the revelations hidden in the mundane goings-on of life – in a way my English studies course couldn’t match. When I decided to stop studying architecture I opted for a humanities BA and that’s where I found anthropology.

Have you always been interested in gaming? How did you get into the gaming world?

I wasn’t big into gaming. Growing up, a gaming console never entered my house and I’d never bought a video game until my twenties. My gaming was limited to Minesweeper, Solitaire, and a game that came free with a non-game-related magazine. We had one computer in the house and I know that if I were a child gamer I’d have been so sucked into the hobby that my poor family wouldn’t have had a chance to use the computer! I discovered the world of indie gaming when I attended the BroForce launch party, which I heard about through a friend. My mind exploded! Who knew this was going on in Cape Town! I knew I had to learn more, so I decided to study South African indie game devs for my social anthropology master’s thesis.

You are a producer at Team Lazerbeam. Take us through this role. What does a video game producer do?

I can’t tell you what the official job spec is for a video game producer. In South Africa, we have a strong legacy of DIY, wearing many hats, and learning from each other within this incredible community we’ve built. Here in SA, one person would fulfil many roles and, as our industry grows, people start to specialise; some studios are now large enough to have separate functions for office management, marketing, human resources, art, animation, programming, game design, all sorts! It’s really hard to be creative and to make sure that any game project remains on track. That’s where a producer comes in. It might differ from studio to studio but, at Team Lazerbeam, I manage project time lines, provide moral support, champion all things quality, and liaise with our publisher.

Have you produced any other games?

This is my first game! I am so excited to be part of Team Lazerbeam. The amazing folks at Team Lazerbeam (we call ourselves a punk band, rather than a game studio) have been my friends since I started studying the game dev scene, so it was a no-brainer when they asked me to join part-time for the last nine-ish months of the game’s production. This is my hobby and a huge passion of mine. Before that, I worked in ed-tech as a learning technologist for four years.

I have never been one to define my role anywhere – I am obsessed with working with other people, helping them to uncover their passions, discovering new things that they are good at, and helping them grow. This sort of inclination leads me to some interesting work and amazing opportunities to adapt, apply my mind, and think critically. I ended up joining Team Lazerbeam because I’d been inserting myself into industry events for years – first, because of my research but, after that, I just genuinely care and want to volunteer because I believe in the indie-game dev community so hard.

What is the hardest part about your (gaming) role and what keeps you going?

The hardest part is also what keeps me going! When you make an indie game you extract a little piece of your heart and your soul, and you mould it into something that other people can engage with, delight in, interpret, and invest their time into playing. On one hand, crafting something truly creative is extremely fulfilling and, as a producer, I have the privilege of enabling game creators to realise their dream game babies. At the same time, when anything goes wrong, the heartbreak is intense. Creating video games requires absolute resolve and faith in your idea and knowing that other people can catch a glimpse into the complex inner workings of your brain is thrilling.

How is Wrestling With Emotions: New Kid On The Block different from the previous game?

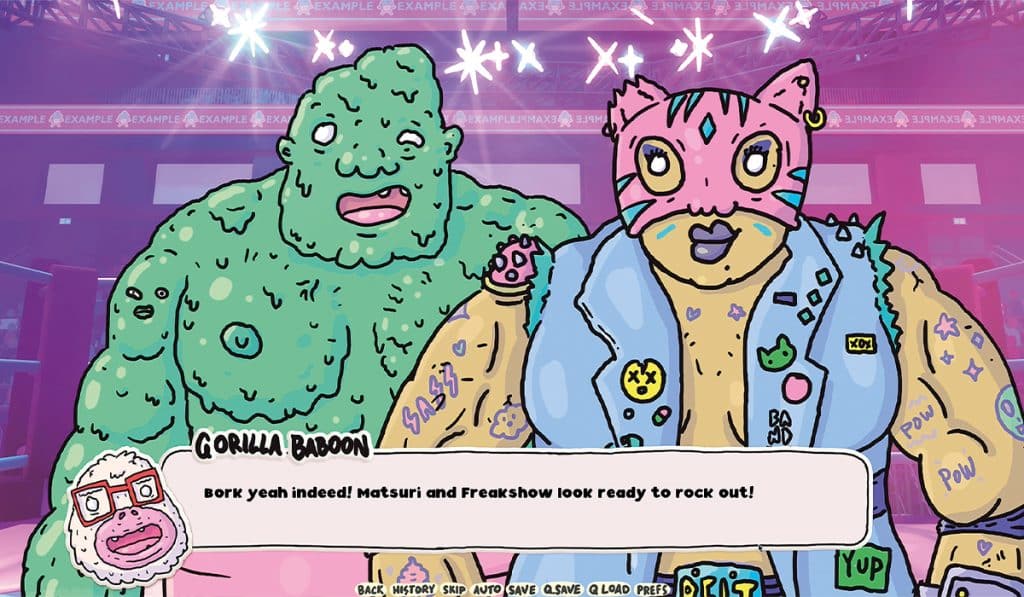

I would say that it’s a step up from the first version. It captures the essence of Wrestling With Emotions but it has a more intricate storyline; complex, fleshed-out characters; heart; and humor. The last two, plus cuteness, stunning graphics, incredible music, and depth, are themes that run through all of Team Lazerbeam’s games. My favourite parts are the music – we have some magical composers on our team! – and the dreamboat wrestlers.

How accommodating is the game-development industry in South Africa given that you are a woman in a male dominated space?

It’s not as overtly male-dominated as one would think. Because I mostly interact with indie game creators, I found that we do a lot of work to undo the toxic elements of the global game industry because norms have not been as deeply entrenched structurally here in SA. Elsewhere in the world, being an indie-game creator is often seen as an act of resistance against the established (often toxic or unhealthy or money-driven) industry. In South Africa, the [professional] industry was started by indies, and we had to be indie out of necessity, building our knowledge, commercial- and creative strategies, and professional networks from scratch.

Everyone is forging a path themselves and we all need each other’s help but, that being said, becoming a game creator full time is hard and you need some sort of leg up. In that way, being a woman, and being someone who is not white, can be a bit challenging not because you feel shut out but because you may not always have the resources, structurally and historically, to take the leap of faith that a game-dev career requires or even to get to the point where you can show up and join in. Once you’re there, I’ve found that there are opportunities to be heard. I have always felt extremely welcome in the industry; I don’t know how I would cope in an international space, though! I feel the local industry is very aware of the social dynamics that go on.

When you are not with Team Lazerbeam, what is your nine-to-five job?

I am a senior knowledge partner at Douglas Knowledge Partners, where I have been working as a writer/editor/ project manager for a year.

Finally, what are your plans and what advice would you give to young people looking to break into the industry?

I actually haven’t planned that far! All I want for myself is a workshop and to make stuff out of wood. If I could do that in five years’ time that would be my dream but, on a serious note, anything that involves helping people is a big yes for me. My advice is to write down your definition of what you want to do, test that and come to meet-ups and gaming events and test out your definition and be open to learning; always test your assumptions. Stay adaptable, innovate, network, collaborate, and incorporate user feedback for iterative improvement.

By: Vuyolwethu Dyasi

Images: Supplied