The sciences have a bad rep: hard, boring, isolating and apparently “not for girls”. Talk about getting it wrong! We speak to three South African scientists at the top of their game.

CURIOUSER AND CURIOUSER…

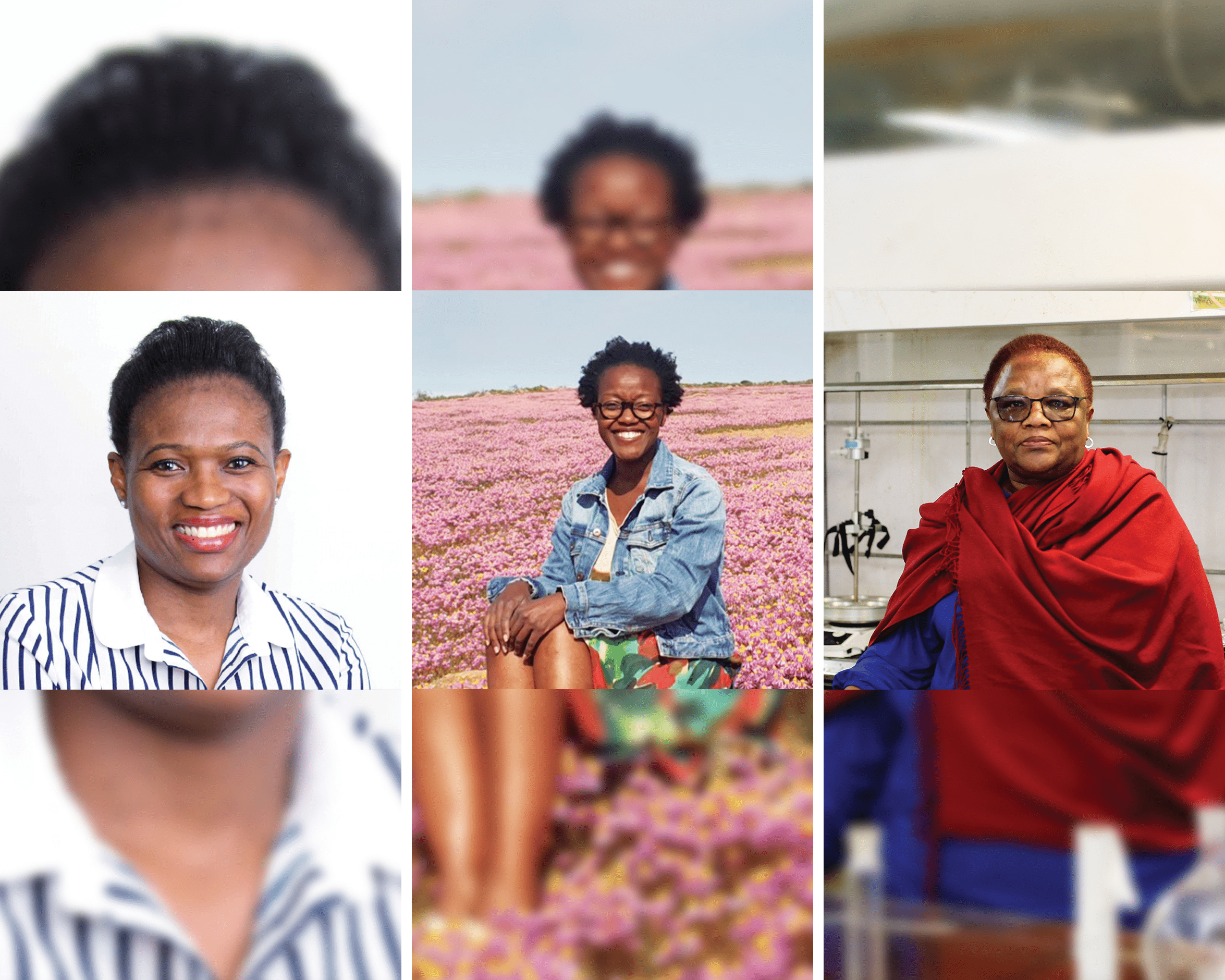

Dr Nolwazi Mkize – Entomologist

Dr Nolwazi Mkize is not one for sitting still. Farming, hiking, cycling, mentoring and studying business could all be on her weekly roster. That’s if she can tear herself away from her true passion: entomology, the study of insects.

Her research has focused on pest control in agriculture but her writing varies from policy documents to an English-isiXhosa dictionary of common insect names found in the Eastern Cape. Having worked in the private and public sector, she is the Head of Regulatory Africa cluster at Bayer CropScience.

“I was drawn to insects out of curiosity. Entomology was introduced as a subject only in the year I started my undergraduate at the University of Fort Hare in 1996. I saw a poster advertising the subject and so I investigated what kind of job it could get me. I wanted something unique and different because I didn’t want to struggle to get a job. My passion grew as I learnt about agricultural pests. So, I can say my career found me rather than the other way around!

“In science, it’s a big thing to discover a new species – especially when you’re not really looking for it! I was interested in solving a pest problem: olive flea beetles. I went to the Western Cape to collect live specimens and while I was on a fi eld trip in Stellenbosch, I noticed some fl ea beetles were an unusual colour. I took the specimens back to Rhodes University to study them and realised there were more differences in their abdomens, which suggested I could be dealing with a different species.

My curiosity grew, so I sent samples to a colleague in Italy. They confirmed that it was in fact a new species! It was a very exciting and rewarding moment, and still is today. “I was drawn to agriculture because of my grandmother, who was a subsistence farmer.

She planted all sorts of things, such as maize and vegetables. I particularly liked harvest time, bagging potatoes and finding a busy spot to sell them in the community. I also enjoyed seeing my granny singing around the fire, waiting for potatoes and pumpkin to be cooked. She would invite everyone to come and eat, especially those that helped during planting. I saved some money and bought myself a small plot to practically start with my passion for agriculture.

“I have three daughters, and my career in science has impacted them in different ways. I asked them how, and Dali says it has opened her eyes to the world of farming and food, and has made her even more curious about farm animals. Lilitha says she is inspired to get her own PhD one day, and Lunathi says that she also wants to follow her passions and dreams like me.

“IN SCIENCE, IT’S A BIG THING TO DISCOVER A NEW SPECIES – ESPECIALLY WHEN YOU’RE NOT REALLY LOOKING FOR IT!”

BEAUTY BLOOMS AROUND US

Prof. Nox Makunga – Botanist

“Take courage to follow your passion – it will only enrich your life and career,” is the sage advice that botanist Professor Nox Makunga would give her younger self. Now a researcher and lecturer in the Department of Botany and Zoology at Stellenbosch University, her high school conviction to become a biologist has come to full fruition.

Her work focuses on the biology of South African medicinal plants, but her research goes way beyond the lab. It has taken her from the plains of the Tankwa Karoo to the hills of Hogsback, and led her to investigate how these plants add socio-economic value.

“Growing up the child of a botanist was wonderful. My father, Oswald Makunga, was a botany professor and the head of a student residence at the University of Fort Hare, so my family spent the first nine years of my life living on the campus. I grew up in an academic environment – we were surrounded by the collegial, unified academic community and all the kids played together. It impacted many of us – we pursued education and so many of those children are now influential in South Africa and beyond.

My dad took us into the university buildings, and sometimes allowed us to interact with some of his experiments – I remember counting maize in the lab with him. He would get very excited about plants wherever we went. If he saw something was flowering, he would stop the car, jump out and go and have a look! This irritated my mother, a high school principal, to no end. But my family had a strong connection to nature. My parents had a nice garden which they took care of, so plant propagation always been a part of my fabric. It was fun – it really was fun!

“Besides my dad, my incredible high school biology teacher influenced me to study botany. Mrs Robinson, or “Mam Rob”, taught at St Andrew’s College in Makhanda while I was at boarding school at The Diocesan School for Girls in the mid-80s. She was such an enthusiastic, creative teacher and quirky in her approach to life and learning. She was so engaged with her subject – she brought lots of specimens to class! She encouraged us to participate in expos, so in Grade 11 I did a project on Ciskei grasslands. My dad introduced me to grassland scientist Prof.

Winston Trollope, who took me to collect the grass and soil samples. I identified and pressed the grasses and classified and tested the soils. Mam Rob helped me prepare this project for the expos. I got a silver medal. Many students, like me, were encouraged by her excitement to pursue biology beyond school. I wanted to be a scientist.

“My career has grown in a totally different environment to that of my father. He had very limited options – as a black person, his only option was the University of Fort Hare. I studied at the University of KwaZulu-Natal and I did my PhD with one of South Africa’s most renowned plant physiologists, Prof. Johannes van Staden. I was at a university that was research-based, while my father was at an institution that emphasised teaching.

Career opportunities during his time were not nearly as open for black people, whereas I studied when things were definitely opening up – I was at university in the early 90s, so I could choose whichever career I wanted; there were no longer constraints on what was available to black people.

“Nature is central to life. But we have been taken away from nature. A large part of South Africans are disconnected to nature because they live in a township that doesn’t have green spaces, or in a high-rise in the concrete centre of Johannesburg. This can cause physical and psychological fatigue. I am very lucky to visit some remote forgotten places in South Africa.

One of my research sites is in the Tankwa Karoo and there’s nobody there in that majestic landscape. I went to Hogsback recently to gather samples, and it had been a long time since I’d been there with my family. It really reminded me how special and rejuvenating the waterfalls and forests are. I couldn’t do this job if I only stared into test tubes!

THE POWER OF PERSEVERANCE

Prof. Tebello Nyokong – Chemist

“In all the sciences all over the world, supervisors and students work together,” says Distinguished Professor Tebello Nyokong. “You cannot say ‘I’ in the sciences,” she adds. You’ve got to say ‘we’, because no one works alone. Research is a team effort.”

This approach clearly works for Prof. Nyokong, who is a prolific researcher and writer with hundreds of scientific papers and numerous international awards to her name. Her focus is medicinal chemistry and nanotechnology, and she is world renowned for her ground-breaking research into a viable alternative to chemotherapy.

“My love for science started in high school. Even though I had a good background in maths and science in primary school, I took the decision not to do these two subjects when I initially began high school. It was a general belief that the sciences are hard and not for girls. When my peers repeated this, I began to believe it. So, I spent three years of high school learning art subjects before switching to the sciences. I really didn’t enjoy my subjects.

More importantly, I found that when I was asked to write a five-page essay, I could easily do it in half a page. I never understood why others would write such a long essay, because I felt I gave the same information in my half page. When I got to university, I chose chemistry because the lecturer was very good. He could make chemistry come alive. Biology soon followed closely as my second choice. “Studying in Canada in the 1980s was a shock to the system, but it made me who I am.

The weather was the first shock: I arrived in winter, the snow was high and I didn’t have the correct clothes. You can never find the right clothes for Canada in South Africa or Lesotho! I completed my master’s in chemistry and then began my PhD, but this time I had my children with me. Yes, I had to be a mother, a student and also a teaching assistant since I needed the money. But I still completed my PhD on time!

All the hard work I had to do while growing up in Lesotho, like shepherding, was paying off. It taught me how to cope with hard work. I love growing my own vegetables, so while in Canada I rented a plot to grow our own vegetables. We grew tomatoes, lettuce, beans and corn ourselves in Canada’s only two months of warm weather! Canada made me. It made me love myself.

The Canadians didn’t believe in African science, so it made me believe in it even more. They made me love Africa. I will fight to make sure that Africans are recognised for their science.

“When I taught university students, I enjoyed teaching the first years the most. I insisted on being the first one to lecture them at the start of the year, when they are still eager and before they get influenced by older students. I wanted to instil my passion for learning in them. I believe in exciting your students about chemistry right from first year and in instilling the values of hard work and passion in whatever they do. I now supervise masters and doctoral students. It’s exciting for them to do research, and I enjoy it with them. We need to share our excitement with the younger students so they, too, can become scientists.

“Awards give scientists the opportunity to educate the rest of the world about South African science. For example, in 2009, the South African National Assembly passed a motion to acknowledge my role in the transformation of science in South Africa. Subsequently, I addressed the Parliament Portfolio Committee on Science. After I was awarded the 2016 Kwame Nkrumah Scientific Award by the African Union, I addressed African heads of states on the importance of science.

When I received the L’Oréal-UNESCO award for Women in Science as a Laureate representing Africa and the Arab States, I was invited to submit papers to top journals like Nature and they also featured the African Science journal in the international journals. I also did over 100 interviews with European media to make sure South African science was visible.