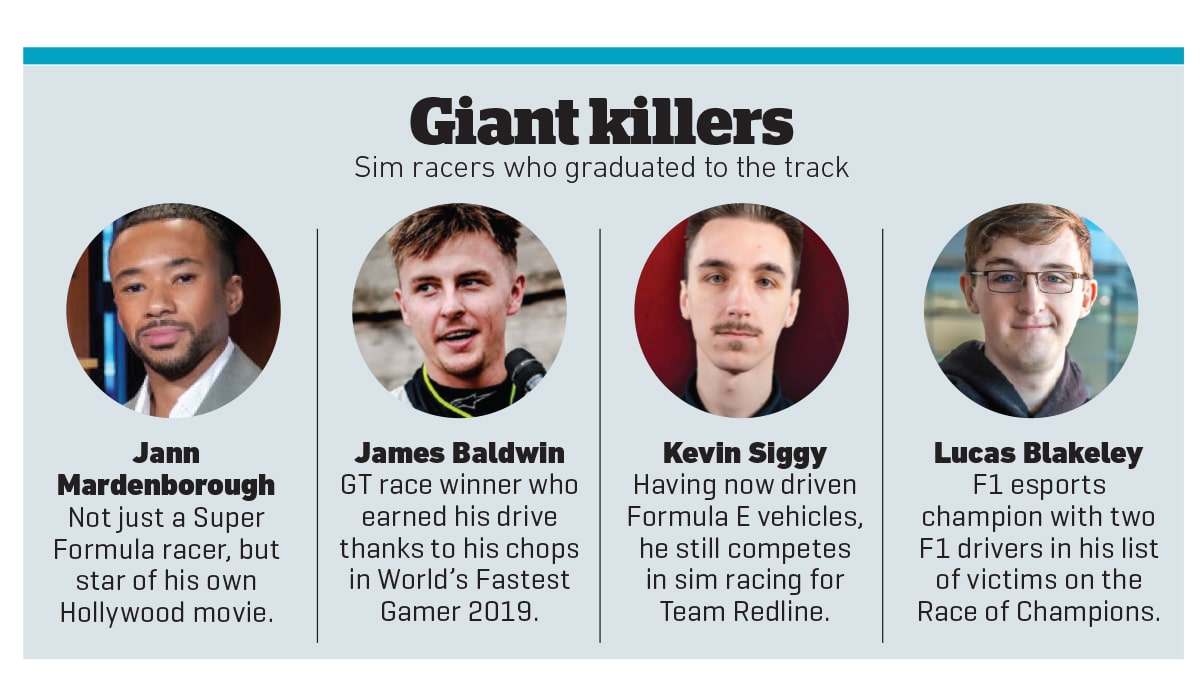

It’s well-documented by now – the skills you develop in sim racing really do translate to the track. Last year’s Gran Turismo movie charted Jann Mardenborough’s journey from hotlapping in the eponymous Sony racer to competing in Super Formula and the World Endurance Championship, but he’s just one of many who have successfully made the leap.

James Baldwin, the 2019 World’s Fastest Gamer winner, has gone on to compete in British GT, winning several races. Numerous F1 drivers have now been schooled by sim racers – Enzo Bonito scaled Lucas di Grassi at the Race of Champions 2019, Valtterri Bottas suffered the same fate at the hands of F1 esports champion Lucas Blakeley, and in 2022 Blakeley did it again against some guy called Sebastian Vettel.

It is settled, then: sim racers are fast. But in reality, they’re not putting down their gamepads and then getting straight into a GT car. They’ve trained their muscle memory using wheels, pedals, and other peripherals that simulate the real environment as closely as possible. The trouble is, you can spend an ever-escalating amount of money on a sim racing rig, and the point of diminishing returns isn’t clear.

At the beginner end, Logitech’s G920 force feedback wheel and pedals bundle offers a great entry point around the R6 500 mark.

Thrustmaster’s TMX bundle does the same for slightly less, if you can live with the plasticky feel. Both can be clamped to any desk, and both are belt-driven force feedback units whose tech introduces a bit more lag and a bit less detail than pricier direct drive wheels, but the jump from controller to budget wheel is significantly bigger than the dainty step from belt-driven to direct drive wheel when it comes to your driving experience.

Spend a few thousand rand more, and you enter a different kind of setup. One typically installed onto a rig rather than clamped to a desk, and where the hardware gets a bit more modular. Direct drive servos from Fanatec, Moza, Thrustmaster and more recently Logitech are the beating heart of higher-end sim racing setups. The feedback’s faster, more powerful and more detailed because you’ve got a direct connection between the actuators generating the sensation and your hands. And since those servos – aka wheelbases – are expensive, they’re usually standalone, able to house a variety of wheels.

Fantatec’s higher end ecosystem is a good example. Once you invest in a direct drive unit, you have a choice of wheel shapes to reflect your discipline – GT, F1, rally or road models designed either for precise, gentle steering inputs or massive, lightning-fast rotations as you see from WRC or drift drivers. From there, you can add shifter and handbrake units, and pedals with different load cells, to build a cockpit that operates and feels like the virtual vehicle you’re driving.

At this level, your hands are engaged in the simulation, but your body isn’t. The bucket seats in sleds made by the likes of Playseat and Recaro put you in the right position to stamp on the brakes, but they’re not actually exerting any forces on you. That’s where electronic actuator platforms like Vesaro’s Quad Motion come in. Priced around R280 000, it’s a base that you build the sled and peripherals onto, and which changes in elevation with a travel of 1.5 inches to mimic the sensations of rolling over a track surface or trackside furniture, or the lateral and horizontal G forces you create with the throttle, brakes and steering inputs.

It is enjoyable, being thrown about on a platform of actuators. But truthfully most sim racers do not train in this way for the simple reason that the significant outlay does not necessarily lead to faster lap times. A consumer-grade actuator platform like this is immersive, but it’s not the most practical setup for someone who trains every day, or anyone who travels and wants to set up their rig quickly in a new location.

Motion generator rigs

Meanwhile, a million kilometres and rands away, is the very top end of simulator hardware:

Dynisma’s DMG. These are the motion generator rigs used by motorsport teams and automotive companies to train their drivers and develop new concept vehicles. And if you have deep pockets and a vast space in which to install their enormous platforms, which feature several metres of lateral and horizontal travel, you can buy one too.

When you accelerate in a Dynisma motion generator, you don’t need to rely on a force feedback wheel to provide the sensation, because your entire chassis shifts backwards on the platform.

Its low-latency electronic actuators respond with incredible agility to model the track surface, providing the tarmac rumble not through your hands, but through your whole body. There’s pitch and yaw motion too, so when the back end of the car starts to step out on you, you’re rotated in the cockpit. Direct drive wheels are great and everything, but they can’t do that.

The only downside, other than the tremendous amount of space required, is that professional motion generators of this calibre cost several million pounds, aka nearly enough to buy an Nvidia GPU. Given that the 5-series cards are expected within months, who has that kind of money to fritter away on sim racing hardware?

Sim racing’s had its hurdles since the lockdown boom, most notably with supply chain, but also in event administration and viewership. However, on a hardware level the demand for both inexpensive rigs and professional equipment remains, and that’s thanks to sim racing’s increasingly accepted position as an entry point into motorsport. Every time a story breaks about someone like Lucas Blakeley beating an F1 driver, some young hopeful buys a cheap wheel and pedals, keen to give it a go. And years later, maybe they end up strapped to a Dynisma rig, being paid for their services.

Text courtesy of Tech magazine