Hop aboard the Wright brothers’ ingenious creation and discover the beginning of modern-day aviation.

It was a brisk December morning in the outer banks of north Carolina, but adrenaline-pumping hearts likely kept the Wright brothers warm as one watched the other take flight in the first successful aeroplane: the Wright Flyer. Until this fateful day, the world’s view of human flight was limited to hot-air balloons and gliders. However, two American men, brothers from Millville, Indiana, swooped in at the start of the 20th century and opened the world’s eyes to the possibility of flight powered by a heavier-than-air flying machine.

Before human flight piqued their interest, the Wright brothers’ first joint venture was a printing business in the mid-1880s. By 1889, Orville and Wilbur had started up a local newspaper called West Side News, which later became the Evening Item and closed after 78 issues. During this time, the brothers also turned their business brains to the growing bicycle craze that was sweeping America. In 1892, the Wright Cycle Company was formed to sell bicycles before servicing and manufacturing its own bicycle model, called the Van Cleve, in 1896.

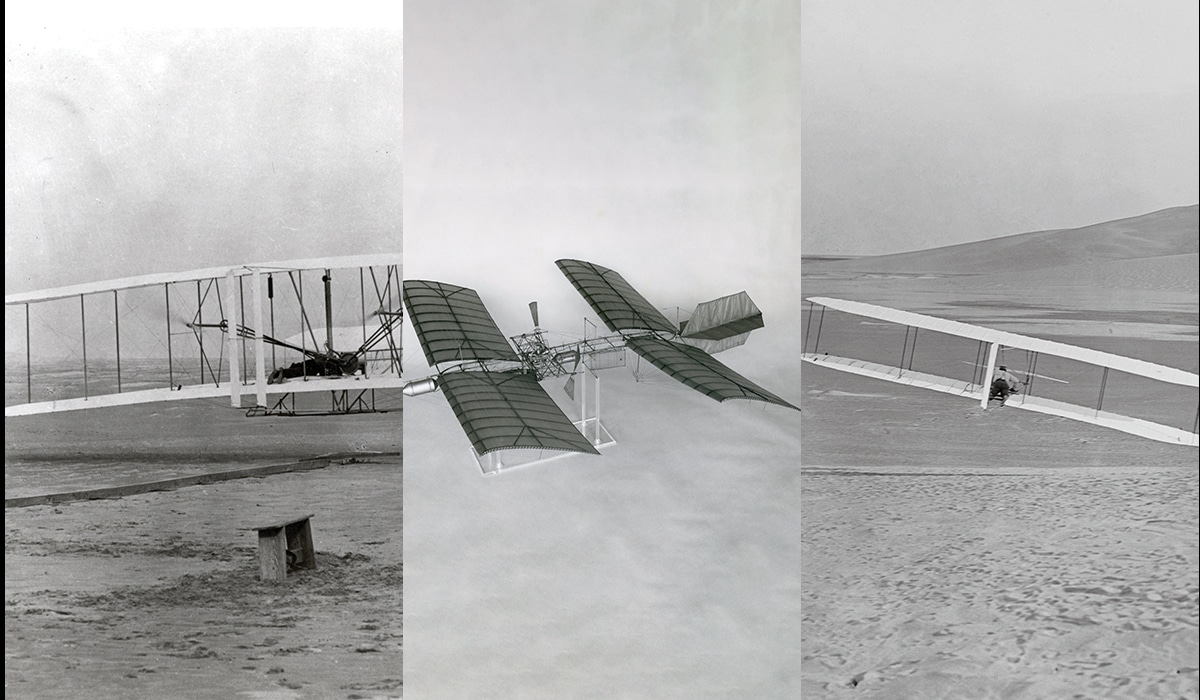

Much like the transition from printing to bicycles, the Wright brothers made a jump into another industry, but this time they looked towards the sky for inspiration. In 1899, after experimenting with designs for kites and gliders, they discovered that when the opposing corners of a long box were pulled together by string, the box would twist.

This was something Wilbur Wright thought could be used to control the way a glider moved through the air. After building a test model, he quickly proved his theory was correct. Within a year, Wilbur had built a biplane glider, with two wings situated on top of each other that could theoretically generate enough lift to carry the weight of a man. However, it wasn’t until 1902, after countless failed flight attempts and design changes, that they succeeded. The 1902 Wright Glider had a wing span of 9.8 metres, a hip cradle for the pilot to operate moving components such as a rear rudder and a front-facing elevator wing to control its pitch. The brothers conducted hundreds of test flights, the best of which lasted 26 seconds, when the aircraft travelled 191.5 metres.

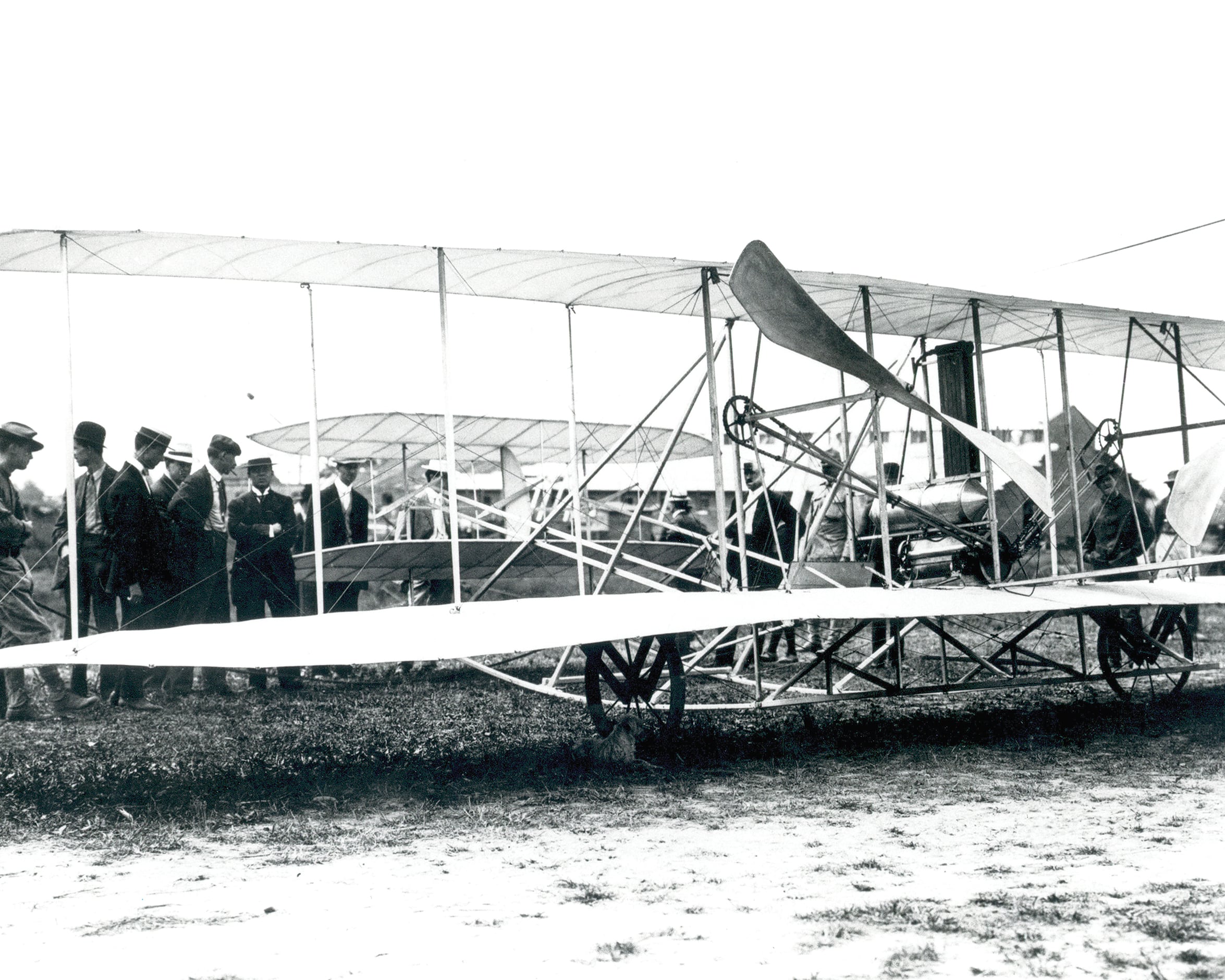

With the aerodynamic construction of their glider mastered, there was just one thing the next generation of flyers needed – a propulsion system. The brothers, helped by their bicycle shop mechanic Charlie Taylor, created a 12-horsepower petrol engine that produced enough power to spin a pair of rotary propellers. The theory was that the propellers would generate enough airflow over the surface of the glider’s wings and generate enough continual thrust to keep the flyer in the air.

On 17 December 1903, after around four years of research, the Wright brothers headed over to Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, to put their latest creation to the test. Four test flights were carried out in total, with each brother taking turns being strapped into the pilot cradle. A rope-and-pulley system was designed to hurl the aircraft along a runway and ultimately into the air for each test. On the first attempt, Orville flew for 12 seconds, travelling only 36 metres before landing, but each attempt was more successful than the previous one, and the final test proved the best of all when Wilbur piloted the flyer 255.6 metres, staying aloft for 59 seconds.

These four remarkable tests were more than enough evidence for the brothers to hold a press conference and announce to the world the astounding achievement of their experiments. However, the success of the engine-powered Wright Flyer remained unseen until 1916, when it was put on display in an exhibition at MIT.

The spat with the Smithsonian

The Wright brothers weren’t the only inventors on the cusp of being the first to build a heavier-than-air aircraft. In 1896, American engineer Samuel Pierpont Langley created the prototype for what could have been the first powered flying machine, called the Langley Aerodrome. By 1903, Langley had built a full-scale manned machine that housed a five-cylinder engine.

However, during two test flights – the final one just days before the success of the Wright Flyer – the Aerodrome was launched into the air and quickly nose-dived into a nearby river. In 1913, the remains of Langley’s Aerodrome were sent to Glenn Hammond Curtiss, the secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, who rebuilt and flew the Aerodrome the next year. He concluded Langley’s creation was in fact the first true aircraft due to its capability to fly. However, after many years of legal and political battling, the Smithsonian retracted that decision in 1942, as the 1914 test flights did not accurately prove the Aerodrome would have flown.

Words: Scott Dutfield

Photography: Alamy/Shutterstock

Also read: How tech can predict, prevent and assist in accidents