Discover the science behind the glitter and sparkle of the pyrotechnics

Whether it is the Fourth of July, Guy Fawkes Night or New Year’s Eve, you are sure to see the sparkling lights of nearby fireworks, followed quickly by their boisterous, climactic explosions. But igniting colourful chemicals and shooting them into the sky is not a new tradition by any means.

The first fireworks were hurtling into the sky in around 600 BCE in ancient China. Ancient alchemists discovered that mixing potassium nitrate, sulphur and charcoal produced a black powder that’s now referred to as the ‘first gunpowder’. When this powder was stuffed into bamboo sticks and ignited, it created the first firework propulsion system. Early fireworks were used to celebrate weddings and births, and even to ward off evil spirits.

Modern fireworks still use black powder, but now incorporate small pellets of packed minerals, called stars, to produce colourful explosions. When the chemicals in the stars are heated, the electrons making up their atomic structures are excited and release energy in the form of different wavelengths of light.

For example, when a copper-filled star ignites it burns a brilliant blue colour. Stars are held within a shell, often concealed within a rocket, and are placed in a launching tube called a mortar. A pile of black powder beneath the shell is ignited, and its combustion generates enough force to send the shell flying into the sky before another charge inside the shell combusts, igniting the shells, and the stars within them. If the stars inside are arranged in a particular orientation or design, the erupting fireworks will also resemble that design. If the stars are arranged to look like a heart in the shell, the resulting firework will also resemble a heart.

Shells come in a variety of different shapes and sizes. In the US, shells are typically spherical, whereas in Europe shells are more cylindrical and stack layers of different stars on top of each other, separated by a portion of black powder, to ignite them in stages.

Of course, the fireworks are not purely visual – there’s also a range of hissing, crackling and booming sounds that will come with any good firework display.

These auditory elements of a firework aren’t necessarily natural by-products of a firework explosion: some are purposefully put into the firework shell. Minerals such as bismuth create crackling sounds, while potassium salts make fireworks whistle as they travel.

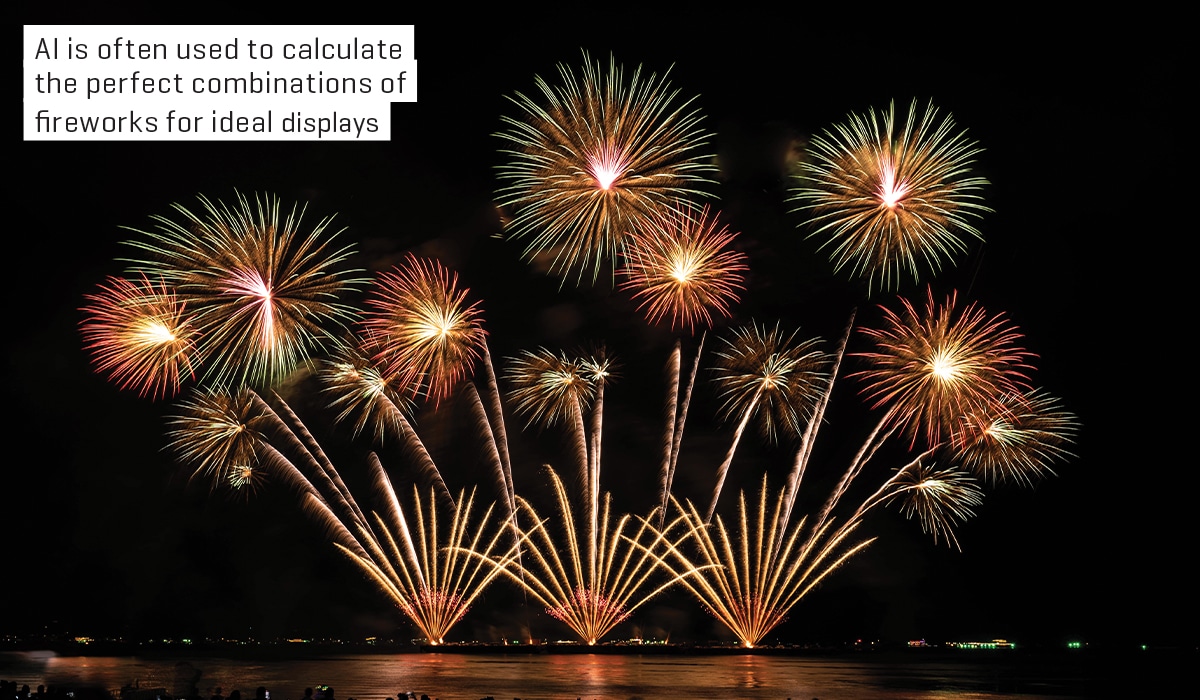

AI-designed displays

Like in many other industries, artificial intelligence (AI) has found its way into the toolset of firework display designers. Along with being able to simulate a digital display, AI is being used to gather data from displays around the world to choreograph new and unique experiences. AI is capable of precisely calculating the optimal timing, position and safety of fireworks to produce a display that’s not only visually exciting, but one that is perfectly synchronised with any accompanying music. It can even be used to respond to changes in the weather in real time, such as adjusting the position of a launching mortar to account for a change in wind speed.

Did you know?

The world’s largest firework shell measured 1.44 metres in diameter

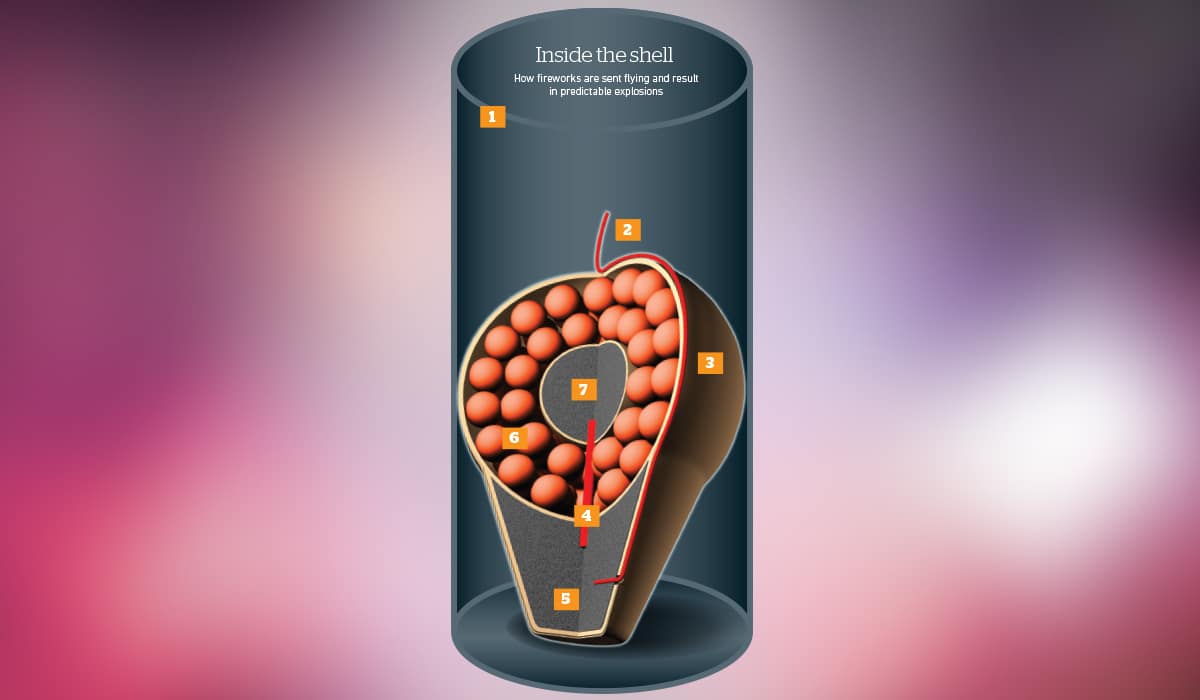

Inside the shell

How fireworks are sent flying and result in predictable explosions

1. Mortar

The launching tube that holds the shell is typically made of strong steel, dense plastic or fibreglass.

2. Fuse

A fuse, typically made of cotton dipped in black powder, is lit and carries a flame along its length to ignite the black powder at the base of the shell.

3. Shell

The exterior of the shell is often made of paper that houses a collection of small colour- producing pellets, called stars.

4. Timed fuse

When the initial black powder is ignited, it also ignites a second fuse within the shell.

5. Lift charge

Underneath the shell is black gunpowder that explodes when ignited, forcefully expanding out of the launching tube and propelling the shell into the air.

6. Stars

Different varieties of powdered metals create the spectrum of colours of a firework when they are ignited.

7. Burst charge

More black powder is packed into the shell, which is ignited by the timed fuse to explode the shell and stars within.

5 fun firework patterns

1. Willow

As well as coloured salt, a large amount of charcoal is put into the stars of a willow firework. When the stars explode, the charcoal burns in trails as it falls.

2. Palm

When larger grains of minerals are used to fill the shell’s stars, it takes longer for them to combust, creating a palm-tree-like effect.

3. Strobe

The compounds used in these fireworks produce a strobing effect caused by the slow-burning fuel repeatedly smouldering and re-ignite following the initial explosion.

4. Comet

A large proportion of charcoal, along with titanium or aluminium, is used to produce long gold and silver tails radiating from a comet firework.

5. Crossette

Unlike your typical fire-

work star, the stars of a crossette firework have a four-sided cavity filled with

a burst charge and capped at one end. When the firework explodes, the star separates in four different directions.

By: Scott Dutfield

Images: Julian Colton/Getty/Alamy/Shutterstock