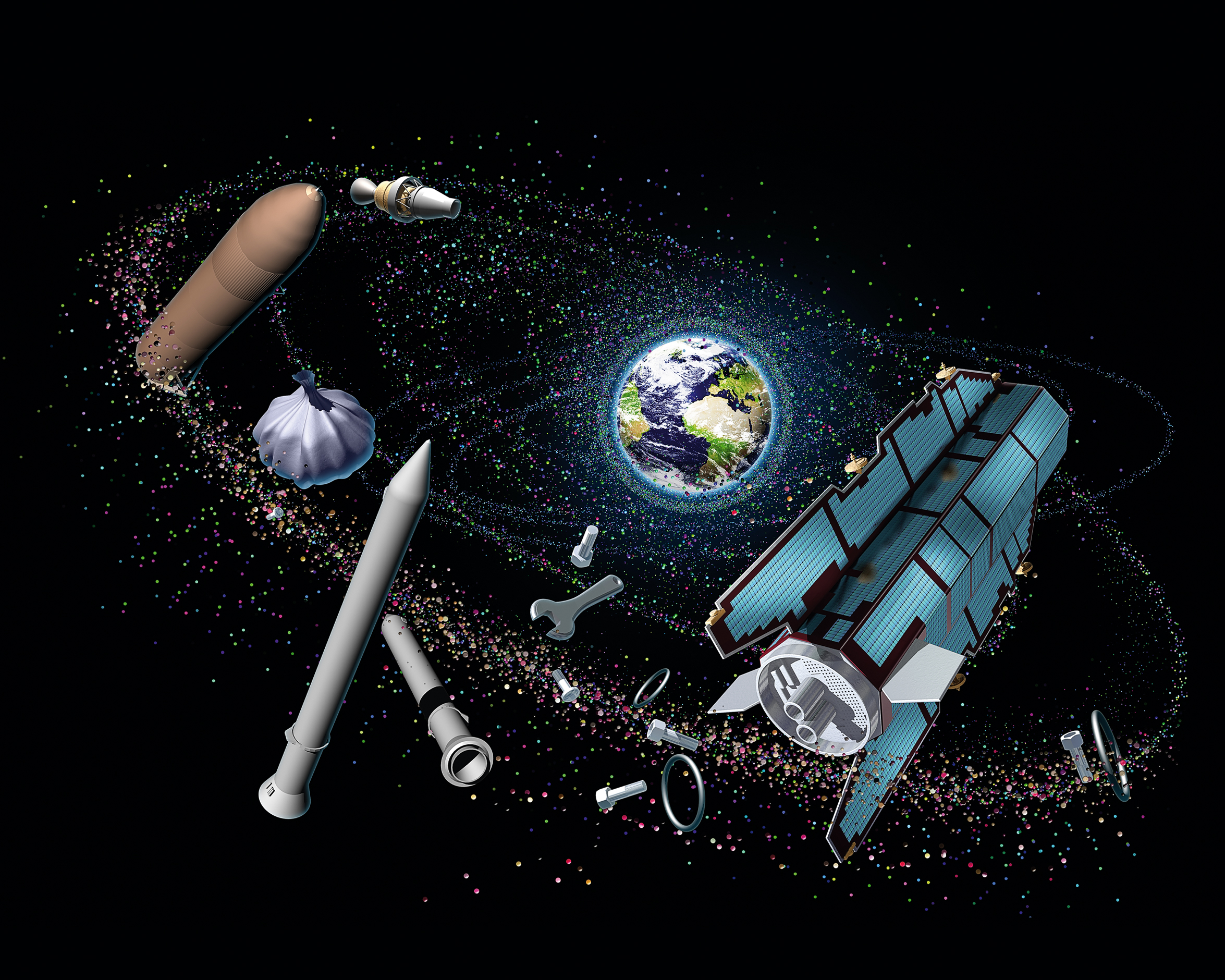

More than 60 years of space flight has cluttered Earth’s orbit with debris. How do we track it, and can we get it back safely?

On 4 October 1957, the Soviet Union launched Sputnik 1, the first artificial satellite to orbit Earth. That historic day also saw another first – the rocket that propelled Sputnik into space detached and became the first piece of space junk. Space junk, or orbital debris, is the common term for any human-made object in orbit that no longer serves any purpose.

It ranges from bus-sized items, such as non-functional spacecraft, to nuts and bolts and dust from engines. Since 1957, the amount of space junk surrounding our planet has steadily grown, to the point where the US Space Surveillance Network is tracking the movement of more than 34 600 objects five centimetres wide or larger.

While the risk to life on Earth is low, space junk poses a significant problem for craft in orbit. It can travel at up to 28 000 km/hour and, at that velocity, even a collision with a piece of debris a couple of centimetres wide could be terminal to a spacecraft.

To prevent its satellites and spacecraft being damaged, in 2007 NASA entered into an agreement with the United States Strategic Command, which tracks the flight paths of thousands of pieces of debris daily via ground-based radar, as well as lidar that measures distance by illuminating a target with a laser and analyses the reflected light.

If the likelihood of a collision is one in 10 000 or higher, NASA is informed and can steer the craft out of the way. The International Space Station has had to make dozens of these evasive manoeuvres since its construction was completed in 2011.

Even if we never launch another item into space, it’s possible that the amount of orbital debris will remain stable until around 2055, and may then increase. This scenario, known as ‘Kessler syndrome’, in which the increase in debris heightens the chance of collisions, creating more debris and causing a domino effect, was proposed by NASA scientist Donald Kessler in 1978.

There are proposals to remove debris, but they are in their early stages. Until we can develop cheaper techniques, international guidelines have been drawn up to prevent further launches exacerbating the problem, including ensuring objects are removed within 25 years of becoming obsolete.

Words By: Alex Dale

Photography: Andrew Mclaughlin